The Dukes of Durham

Family on a Small Farm

“I have made more furrows in God’s earth than any man forty years old in North Carolina.”

In December of 1820, Taylor Duke and Dicey Jones Duke welcomed their eighth child into the world, a boy they named Washington. The family lived on a farm in Orange County, North Carolina in what is today Bahama. Born into modest circumstances, Washington Duke would eventually become a pioneering industrialist and prolific philanthropist.

In 1842, Washington Duke married Mary Caroline Clinton and moved onto land given to them by her family. The couple had two sons, Sidney Taylor Duke (b. 1844) and Brodie Leonidas Duke (b. 1846). During this time Washington’s younger brother, Robert, came to live with the family and is listed as a student on the 1850 census. The census also lists twenty-five year-old Alexander Weaver as a member of the household. It is believed that he was a free black laborer working for the Dukes.

Just five years into their marriage, Mary passed away, leaving behind Washington and their two young sons. While relatives cared for the boys, Washington worked his land, expanded his land holdings, and began constructing a four-room house.

In 1852 Washington remarried and moved his family into the house he had built, known today as Duke Homestead. He met his second wife, a young woman from the Haw River area, named Artelia Roney, at a Methodist revival. The pair had three more children: Mary Elizabeth Duke (b. 1853), Benjamin Newton Duke (b. 1855), and James Buchanan Duke (b. 1856) whom everyone called “Buck.”

In 1855, Washington Duke purchased a young girl named Caroline who was about 11 or 12 years old. Caroline remained enslaved at Duke Homestead from 1855 to approximately 1860. Washington Duke also rented the labor of an enslaved man named Jim in the early years of the Civil War.

Tragedy struck the Duke family again in 1858. Washington’s oldest son, Sidney, fell sick with typhoid fever. Artelia caught the disease while caring for him and the two died within ten days of each other. Washington Duke never remarried. He continued to farm his property with help running the household from Artelia’s family and the use of enslaved labor.

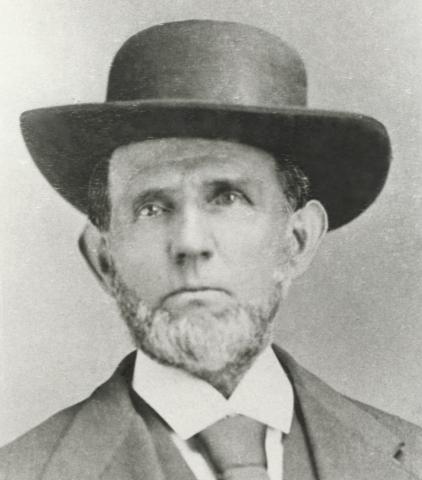

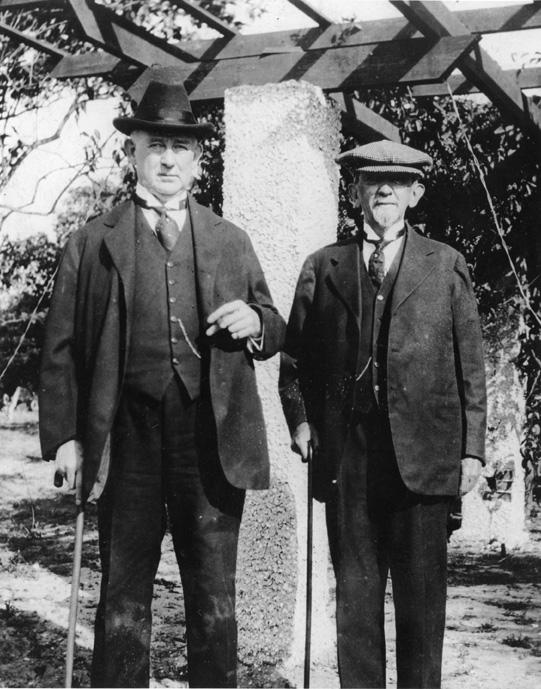

Left: Washington Duke on the porch of his old homestead in 1904. (Courtesy J.B. Duke Papers, Box 57, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

A Country at War

When the Civil War began in 1861, Washington Duke was in his early forties – too old to be drafted into military service. By 1863 the Confederate government faced a shortage of troops. The Confederacy enacted conscription laws that made men between the ages of 18 and 45 eligible for active service. By 1864, 43-year-old Washington Duke and 18-year-old Brodie Duke were pulled into the war – Washington into the Confederate Navy and Brodie into service as a guard at Salisbury Prison.

Before going to war, Duke decided to sell all his farm belongings and converted his assets into cured tobacco leaf. Duke’s younger three children went to live with their Roney grandparents in Alamance County during his absence. It is not known what happened to Caroline or Jim during or after the Civil War.

At the end of his short military career, WashingtonDuke was captured by Union forces and briefly imprisoned in Richmond, Virginia. At the end of the war, the Federals released and shipped him to New Bern, North Carolina. With no money or transportation, the veteran walked back to his homestead – a distance of 135 miles.

New Beginnings and New Business

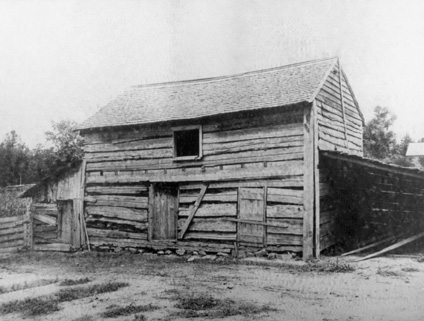

Washington Duke returned home after the war and began what would grow to be the largest tobacco manufacturing business in the world. The start, however, was humble. Duke converted his corn crib into the family’s first factory, where he and his children began manufacturing pipe tobacco.

They named their business "W. Duke & Sons" and called their product “Pro Bono Publico” - Latin for "For the Public Good." Washington took the manufactured leaf on a peddling trip into eastern North Carolina. The trip was a success; merchants in small towns and villages were his best customers.

Washington Duke’s business grew quickly, and he converted another building into a factory. By 1869, W. Duke & Sons was successful enough to warrant a new factory building designed specifically for tobacco manufacturing. This building, referred to as the Third Factory, stands today at Duke Homestead State Historic Site.

By 1873, the Dukes were producing around 125,000 pounds of smoking tobacco annually. By 1874, their business had grown to the point where the family was ready to move off the property and into the growing city of Durham.

Duke's Second Factory which operated until 1869. (Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina)

The Move into Durham

“As for me, I am going into cigarettes.”

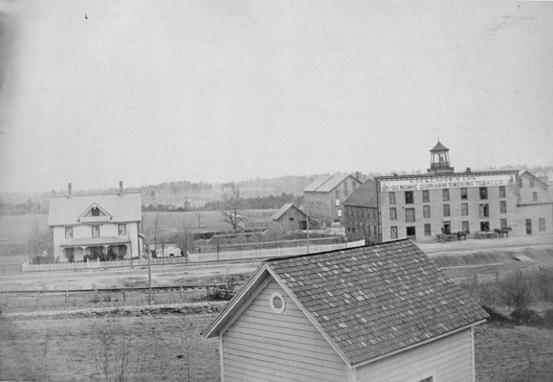

When Washington Duke moved his business into downtown Durham in April of 1874, he purchased two acres of land next to the railroad running through town. There Duke and his sons built a new factory, with Benjamin and Buck given equal partnership in running the company. After adding an outside partner, the business became W. Duke, Sons and Company. While the sons assumed much of the responsibility running the company in Durham, Washington Duke traveled throughout the country promoting the company's products.

However, the Dukes were not the only tobacco manufacturers in town. Around what had once been simply "Durham’s Station" – a small stop on the North Carolina Railroad – tobacco warehouses and manufacturing businesses had sprung up since the end of the Civil War. More and more people were moving into Durham seeking work, and the town was growing in population and diversity.

W. Duke and Sons Factory on Main Street in Durham next to Washington Duke's new home.(Courtesy Duke Homestead State Historic Site, Division of State Historic Sites and Properties, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources)

It was the closeness of competition, particularly from Blackwell’s Bull Durham pipe tobacco, that led youngest son, Buck Duke, to start manufacturing cigarettes in 1880. In this pivotal year for the business he founded, Washington Duke retired at the age of 60. He spent his retirement becoming more involved in the local community through the Methodist church and local politics.

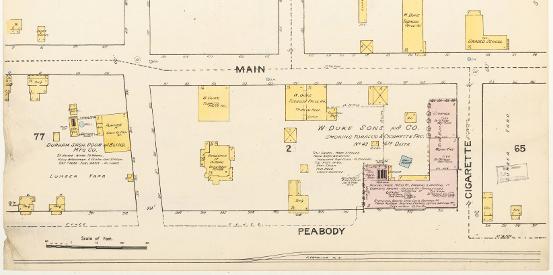

Map of The Duke homes and factory buildings in Durham in July of 1884.

Cigarettes came to the United States around 1860 after becoming popular in Europe. Early hand-rolling methods used in cigarette production were slow and tedious; an expert could roll only about four per minute. W. Duke, Sons and Company and other tobacco firms began to hire immigrants from Eastern Europe who were skilled cigarette rollers. As cigarettes grew in popularity, tobacco companies began the search for a quicker, more efficient mechanical method. In 1884, Duke’s company decided to take a chance on Bonsack cigarette rolling machines, leasing two of the devices for their Durham factory.

With an eye on the future, James B. Duke expanded the company with a branch in New York and continued to invest in Bonsack machines. By 1885, W. Duke, Sons and Company was emerging as the leading cigarette producer in the country, fueled by mechanization, advertising, and Buck Duke’s leadership.

Monopoly

By 1887, most of the tobacco industry fell under control of the five largest cigarette manufactures, which included the Dukes and their four most important competitors: the Allen and Ginter Company of Richmond, the F. S. Kinney Company and the Goodwin Company both of New York, and William S. Kimball and Company of Rochester. For James B. Duke, now president of W. Duke, Sons and Company, the solution to this competition was a merger of the companies.

After discussing the merger, and following a period of trying to outspend one another on advertising, the large rival firms agreed to Duke's plan. In 1890, the five principal companies united to form the American Tobacco Company, with James B. Duke as the company's president. This combination quickly became known as the "tobacco trust," because of its almost complete monopoly of the tobacco trade.

In 1890, James B. Duke controlled the largest tobacco industry in the world, and the combined firms continued to grow in the next two decades. By the turn of the century, however, public anti-trust sentiment increased rapidly in the United States. A Supreme Court ruling dissolved the American Tobacco Company in 1911. Four major tobacco corporations emerged from the separation of the trust: a new American Tobacco Company, Liggett and Myers, P. Lorillard, and R. J. Reynolds.

James Duke (left) with brotherBen Duke (right). (Courtesy J. B. Duke Papers, Box 56-A, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

From Trinity to Duke

"Tell them every man to think for himself."

After retiring from the tobacco business in1880, Washington Duke began working to bring a small Methodist college to Durham. Trinity College, located in Randolph County, was adopted by the Methodists of North Carolina in 1856. By the late 1880s, the school barely had enough money to operate. The Methodist Church in North Carolina did not have the funds to support the institution, and the school lacked the leadership of a strong president. With the appointment of Pres. John Crowell in 1887, things began looking up for Trinity. Ben Duke gave the struggling institution $1,000 that year, beginning the family's association with Trinity.

The new president aimed to grow the struggling school to compete with top universities in the nation. Part of this vision involved a move from rural Randolph County to a city.

Durham, the quickly-growing factory town, sought a college. Durham bid against Raleigh for a Baptist Female Seminary (what became Meredith College), and he lost. Washington Duke felt Durham’s embarrassment at this loss, and turned his focus to Trinity College. He offered to match Raleigh’s bid of $35,000 and provide an additional endowment of $50,000. Julian Shakespeare Carr, another prominent Durham businessman, provided fifty acres of land as a site for the school. The college accepted Durham’s bid. Work on the new campus began in 1890, and it opened to students in 1892.

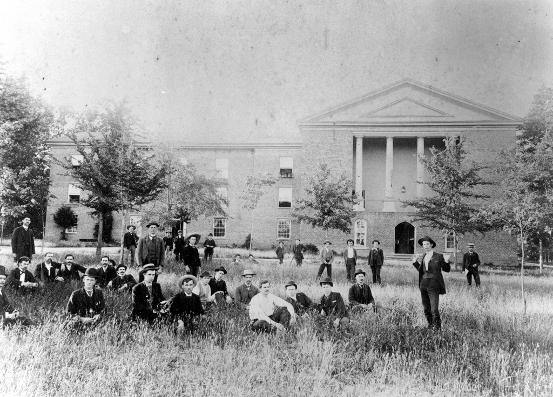

Trinity College student body, 1891 (Courtsey David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University

The Duke family continued to support Trinity in its early Durham years, with Washington serving on the building committee and Ben and Buck Duke lending monetary support. Trinity was not the only institution to receive the support of the Duke family in the late 19th century. The family regularly gave to the Oxford Orphan Asylum and Kittrell College for African Americans. Long before the existence of Duke Hospital, the family became heavily involved with both Watts and Lincoln Hospitals.

As for Trinity, Washington Duke endowed the school with $100,000 in 1896. Though he refused to have the school renamed as "Duke College," Washington informed Trinity that the money did come with the condition that the college "open its doors to women, placing them on equal footing with men."

The Trinity student body celebrates Washington's gift to the school outside of his home in Durham.

(Courtesy J.B. Duke Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

Trinity College Campus in Durham 1903 - 1909 (Courtesy: Duke University Archives. Durham, North Carolina, USA.)

The Duke family’s support helped Trinity to grow its student body and campus, as well as the quality of the faculty and fields of study. In addition to funding, the family supported the academic freedom of Trinity College’s professors. Members of the Duke family also began to attend Trinity, with both Ben Duke's son and daughter graduating in the early 1900s.

Through the 1910s, members of the Duke family planted the seeds of what would become "The Duke Endowment." However, it was not until 1924 that James B. Duke signed the indenture for the endowment, handing over $40,000,000 to its trustees. With the endowment, Trinity College became Duke University. Today visitors to Duke’s East Campus will see a sculpture of Washington Duke, sitting in a chair and watching over the school he and his family helped to build.

EPILOGUE

Washington Duke passed away in 1905 at the age of 84. He endured hardship, poverty, and war. He saw tremendous success and wealth. He enslaved two people and served the Confederacy. He gave generously to numerous relatives and institutions, setting an example of philanthropy that resonated through generations of the Duke family. Born before Durham existed, Washington Duke’s influence, as well as that of his children, can be seen throughout the Bull City today.

You can see how it all began by visiting Duke Homestead State Historic Site.